Archeologie.culture.fr collection

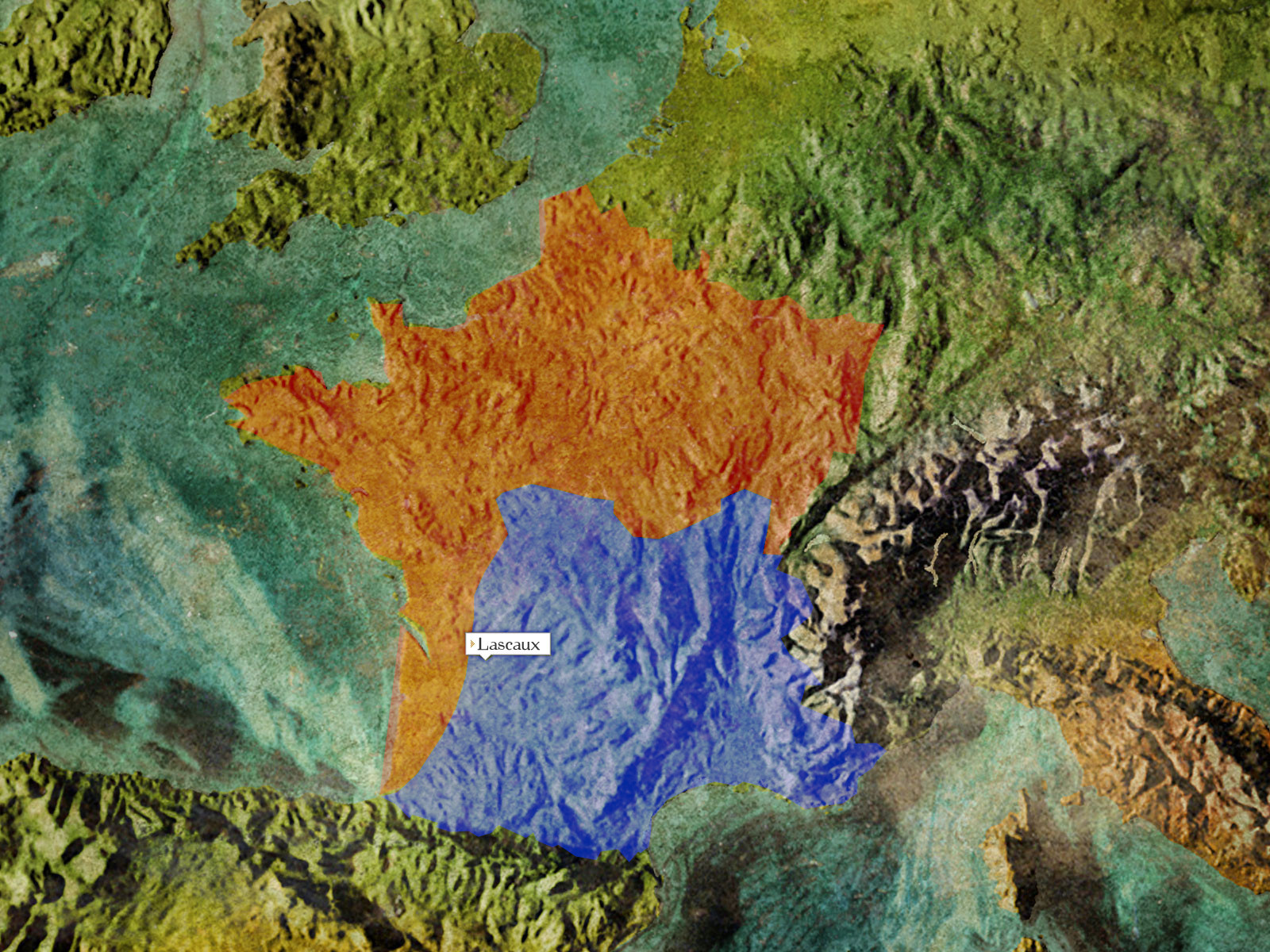

Lascaux cave

September 12, 1940

Montignac, Dordogne. Free Zone.

We are in the midst of World War II, at the end of summer 1940. France is experiencing some of its most dramatic hours. Nothing suggested a shift in focus from the tragic events of the time. Yet, a major archaeological discovery was about to capture everyone’s attention for a while.

Just a few days earlier, while chasing his dog, Robot, the young Marcel Ravidat made an intriguing discovery. A hole had opened in the ground near the Lascaux estate. However, he lacked the time and equipment to explore further.

So, he returned with three friends: Jacques Marsal, Georges Arniel, and Simon Coencas, two Parisian refugees fleeing the occupation and the war. Together, they explored what they believed to be a secret underground passage leading to the nearby mansion.

After enlarging the opening and descending onto a cone of rubble at the bottom of the cavity, they began to explore what appeared to be a large cave with several branching tunnels.

Equipped with a hastily improvised lamp, they traverse the first chamber, approximately thirty meters long, shrouded in complete darkness. They enter a narrow corridor, which would later be named the Axial Gallery. The walls close in around them.

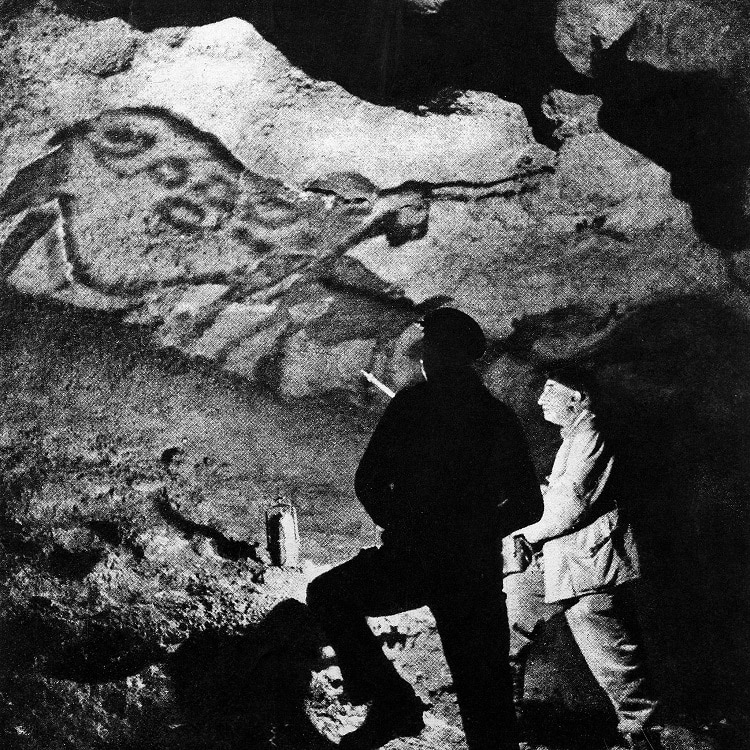

Suddenly, by the light of their dim lamps, they are confronted with a stunning sight. They see, illuminated by the narrow walls, magnificent depictions of animals unfolding on the cave's surfaces.

They explored all the branches of the cavity, with the walls revealing a fantastic array of animals. Their exploration was halted by a dark hole leading to further extensions of the cave.

They shared their adventure with their teacher, Léon Laval, who descended into the cave himself on September 18. Abbé Henri Breuil, a refugee in the region, was informed of the discovery and made his first visit to the site on the 21st of the same month.

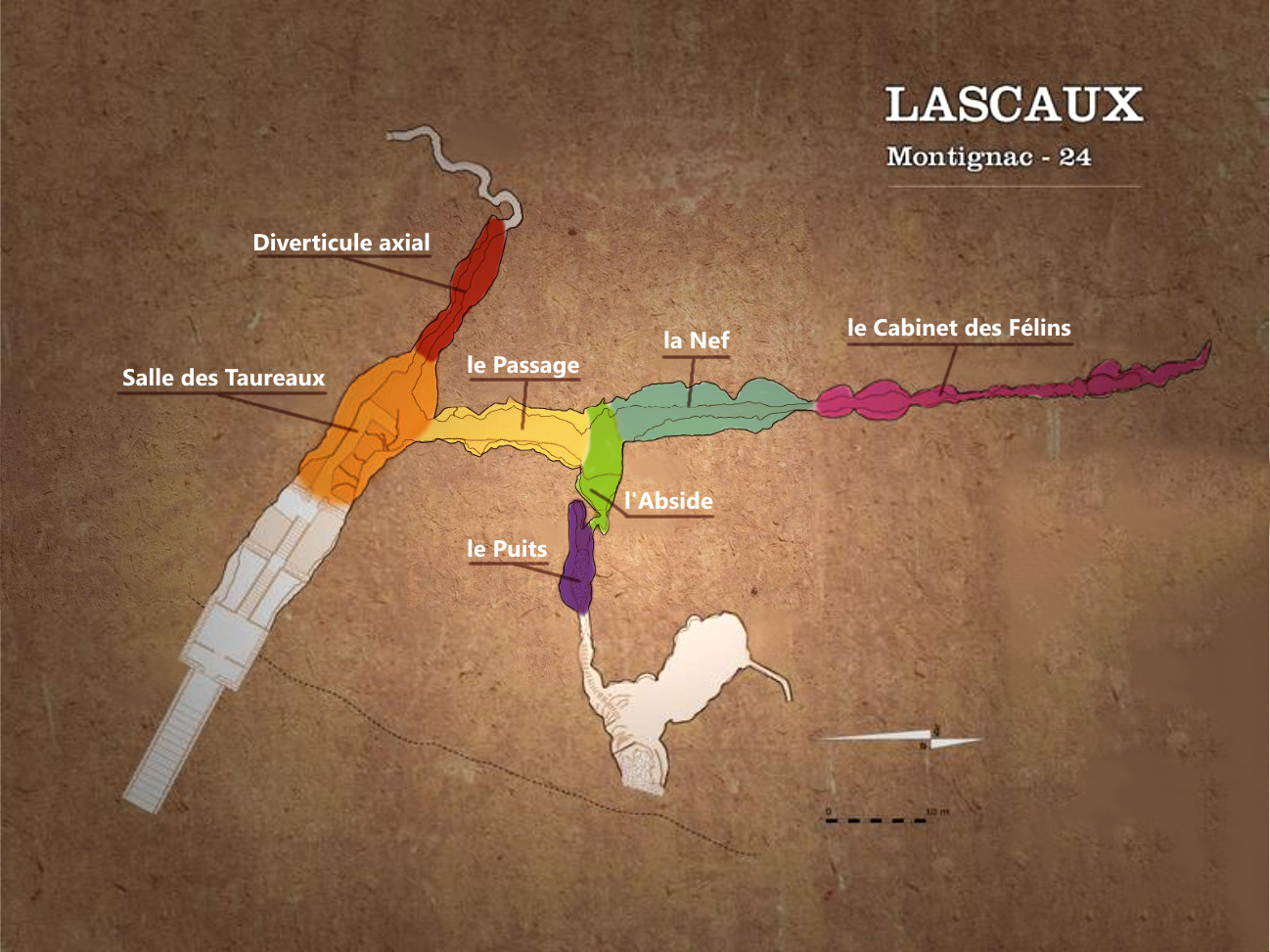

They have just discovered the "Sistine Chapel of Prehistory." The total extent of the galleries accessible to humans does not exceed 235 meters. Traditionally, the sanctuary is divided into seven decorated sectors: the Bulls' Chamber, the Axial Gallery, the Passage, the Nave, the Feline Chamber, the Apse, and the Well. Exploration of this environment follows three main routes. One connects the vestibular zone, the Bulls' Chamber, and the Axial Gallery; another links the Passage, the Nave, the Mondmilch Gallery, and the Feline Gallery. The final route traverses the Well and the Great Diaclase, beyond which a significant collapse marks the junction with the Sand-filled Chamber.

The Bulls' Chamber

Three animal themes compose this vast ensemble: the horse, with 17 individuals; the aurochs, including eleven cows and bulls; and the stag, with six representatives. These themes recur throughout the various subterranean spaces of this sanctuary. The bear is exceptionally present.

To facilitate reading, this composition is divided into two panels: the left wall panel, known as the Unicorn Panel, and the right wall panel, known as the Black Bear Panel.

The Unicorn

Upon entering the Rotunda, one's gaze is drawn to an animal with strange forms, the Unicorn. In a leading position, it appears to push all the animals on this wall towards the back of the gallery.

This figure features wavy lines that might suggest a feline presence. With its square head, prominent shoulder, swollen belly, and robust legs, it would seem to support this interpretation. However, two straight horns extending a third of the figure's length suggest categorizing this animal as a mythical creature. Various interpretations have been proposed, but none are currently satisfactory.

Black Horses Frieze

In front of the Unicorn, a frieze of eight black horses stretches for 9 meters towards the back of the cavity. These horses, whether complete, partial, or limited to a single anatomical segment, appear to move along the same ground line, marked both by a change in the surface color and by the return of the wall created by the bench. The technique used for the entire frieze is consistent: blowing and stenciling.

The first horse was originally complete. Due to deterioration of the surface, a large flake detached from the wall, taking part of the painting with it. On this flake, now located at the base of the panel, the outlines of the head and neck can still be seen. Another complete horse, the fourth horse, situated in the center of the frieze, is depicted in extension, with only the hind legs resting on the imaginary ground line. Its massive neck contrasts with its reduced head. The mottled appearance of its coat is due to the differential preservation of pigments, better in the concavities than on the protrusions of the rock. Several horses are incomplete, limited to the forequarters (second horse), the head, neck, and start of the back (third horse), or a faint silhouette including the head, neck, and start of the back (fifth horse). The seventh and eighth horses are only sketched.

The Axial Gallery

In this passage, about thirty meters long, the figures are distributed across both walls. On the right, there are three panels: the Chinese Horses Panel, the Falling Cow Panel, and the Red Panel, featuring two horses and a bison; on the left, the Red Cows Panel, the Great Black Bull Panel, the Hemione Panel, and, at the end, the Reversed Horse Locus. The decoration includes 161 graphic entities, of which 58 are figurative representations, primarily animals; 46 are geometric signs, including quadrangular, tree-like, straight, interlocking elements, dotted patterns, or cruciform shapes. There are 57 indeterminate figures that could be interpreted as signs or sketches of animal figures.

A Naturalistic Approach

The Chinese Horses depicted here, three in total, feature prominently in many discussions of parietal art. These figures reflect a more naturalistic approach to form, as well as a closer observation of coat patterns. The overlapping of solid colors, created from contrasting shades of black and yellow, allows for a more accurate reproduction of the coat's chromatic variations.

Similarly, the red cow with a black head depicted on the opposite wall demonstrates a high degree of unity among the representations of female aurochs. The line brushed above its back is seen as a correction, a second intervention intended to address the overly compact appearance of the original solid color. This approach attests to the artist's commitment to achieving excellence in their work.

Animated Frescoes

In this space, we find one of the most accomplished figures in the Lascaux bestiary: the Falling Cow. In addition to the abundance and quality of anatomical detail, it features a rarely reproduced animation in prehistoric iconography, with a twisted body and hind legs pressed against the abdomen. To mitigate the challenges of using a brush on a coarse surface, the body’s outline, head, and limbs were traced using red and black pigments. Only the horns and muzzle were detailed with a brush.

Another painting technique used is juxtaposed punctuation. This technique is notably found on two confronting ibexes at the back of the space. The lines of the black ibex are particularly precise compared to the other figures at this site. The graphic quality of its yellow counterpart is noticeably lower.

The Great Black Bull can be considered the most emblematic work, not only of Lascaux but also of all Paleolithic decorated caves and shelters. While the fresco impresses with its imposing depiction of the bull, the discerning eye will recognize hidden forms within the bull’s black coat. Red images of two cows can be seen, as well as four yellow protomes of aurochs, with their horns being the most visible, protruding from the back of the Great Black Bull, whose contours conceal much of the figure.

The Bear Panel

Upon reaching the end of the Axial Gallery, we must return to the Bulls' Chamber before we can continue to the Passage site. While the left side of the wall is notable for its depiction of the "Unicorn," the right side is equally unique for its rare representation of a Black Bear.

The uniqueness of this bear representation lies in both its rarity and its concealment within the broad black area of the third bull's belly. Total overlays are indeed rare. However, the head and shoulder of the bear, as well as its right hind leg, drawn with three claws, emerge from this ventral area. The image treatment allows us to distinguish the hue used for the aurochs from that of the bear and to discern the graphic outline of the bear, which is missing only the forelegs and the ventral line. The figure is later than the bull; it was created by spraying, with the tip of the nose, the contour of the ears, and the three claws done with a brush. Its muzzle is comparable to that of some horses.

The Passage

The Passage connects the Bulls' Chamber to the Nave and the Apse. It is characterized by a high density of representations that are often challenging to interpret. Several hundred figures, including 385 precisely counted and identified, are found here: horses, bison, ibexes, bovids, stags, and various signs such as hook shapes, crosses, and quadrangular forms.

The Rolling Horse

Some animal figures in the Passage are notable for their animation or the treatment of anatomical segments. These characteristics are evident in the Equid with the turned leg, which occupies the center of a composition featuring about ten equids. Another example is the Rolling Horse. It shares this very rare animation with the Falling Cow, a figure from the Axial Gallery. To facilitate interpretation, its contours have been intentionally highlighted. While the forequarters show no particular features, the entire rear, including the rump and hind legs, has undergone twisting. This movement may not be a result of a fall, like the aurochs in the Axial Gallery, but rather a specific action of some animals rolling on the ground or preparing to get up.

The Nave

The left wall features four panels: the Seven Ibexes Panel, the Imprint Panel, the Great Black Cow Panel, and the Back-to-Back Bison Panel. The right wall is occupied solely by the Swimming Stags Frieze. The slope of the floor has led to the distribution of the panels on different levels. The figurative themes include horses, ibexes, stags, bison, and aurochs, with very different proportions where the equids, as in every sector of the cave, overwhelmingly dominate the fauna with 27 individuals here. In contrast, the aurochs, notable for its massive silhouette and central position in this vast composition, is represented only once, while the ibex is depicted nine times, the bison five times, and the stag six times.

The right wall of the Nave is occupied solely by the Swimming Stags Frieze, while the left wall features four panels. The figurative themes include horses, ibexes, stags, bison, and aurochs, with very different proportions where, as in every sector of the cave, the equids overwhelmingly dominate the fauna, with 27 individuals represented here. The slope of the floor has led to the distribution of the panels on different levels. The figurative themes are divided among horses, ibexes, stags, bison, and aurochs, with horses again dominating the fauna with a total of 27 individuals. In contrast, the aurochs, notable for its massive silhouette and central position in this vast composition, is represented only once, while the ibex appears nine times, the bison five times, and the stag six times.

The Heraldries

The quadrangular signs on the Great Black Cow panel, commonly referred to as "Heraldries," have distinct characteristics that set them apart from other similar figures. Each entity is constructed from juxtaposed colored areas in square or rectangular shapes. An engraved line completes the partitioning of these figures. The colors are the same as those used for the figurative representations, although a purple hue appears only on two of these signs. It is noteworthy that the ends of the hind legs and the tail of the black aurochs are in contact with the upper left edge of each of these signs. Various interpretations have been proposed: grids, hunting traps, tribal symbols used as armoiries; however, in this context, none fully satisfies scholarly scrutiny.

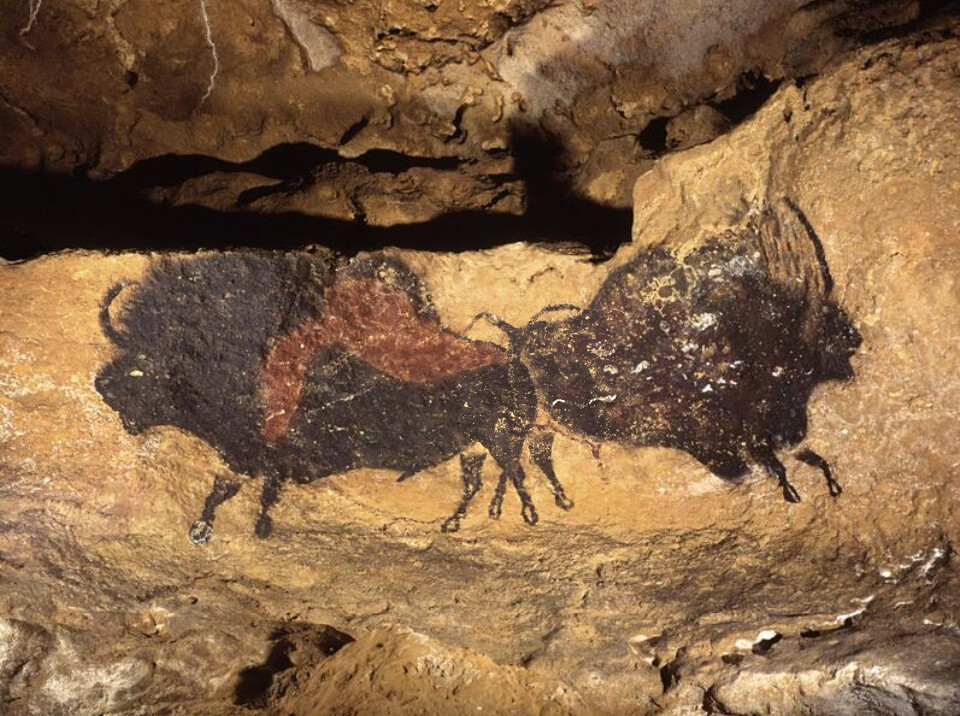

The Back-to-Back Bison

This diptych of back-to-back bison concludes the long succession of panels that adorn the left wall. Its originality lies not only in the proposed animation, with two mirrored male bison, but also in the accumulation of graphic conventions used to emphasize the fleeing movement of the two antagonists in this composition. In this perspective, it is noticeable that the legs in the background are detached from the body, unlike those in the foreground. A gap separates the two rumps, bringing the bison on the left to the forefront. The forelegs are more detailed than the hind legs, with a deliberate degradation of the forms simulating their distance from the observer. The wall itself contributes to this relief effect of the figures; its incline towards the observer enhances the fleeing effect given to the composition.

The Feline Gallery

The Feline Gallery extends over approximately 25 meters. More than 80 figures have been recorded here by André Glory. Of the 51 animal figures in this gallery, horses dominate with twenty-nine individuals, followed by bison with nine, ibexes with four, and stags with three. No aurochs are present. The felines hold a more prominent place here compared to the rest of the cave, with six individuals represented. The distribution of the figures is uneven; 90% of them are located in the first few meters of the passage, which is the narrowest segment of this area.

Feline

The feline theme is not frequently represented in Paleolithic parietal art, with the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc cave being a notable exception, and it often occupies a special place within the sanctuary. Most often, felines are found in the most remote areas; those in Lascaux adhere to this convention. There are six of them, distributed on either side of the entrance to the gallery, in a rigorously symmetrical composition. On each wall, two are directed towards the back, and the third towards the entrance. Another characteristic that aligns them with other felines in this domain of parietal art is the average quality of the graphic depiction.

The Elevated Hut

The term "Elevated Hut," given by André Glory to this geometric entity, evokes attempts at interpretation based on ethnographic comparison. This form is unique in Paleolithic parietal iconography. It obscures the neck of a black equid, whose head is turned to the right, and integrates into a series of long subparallel striations.

Horse Seen from the Front

The iconography of the Feline Gallery offers some distinct features, not only through the themes represented—such as the felines and certain signs like the "Elevated Hut"—but also by the presence of a horse seen from the front. Although its depiction is relatively simple, with four subparallel lines representing the forelegs, the head is particularly well-rendered, leaving no doubt about its interpretation. This horse is positioned above two opposing felines, within a collection of engraved lines that also include bison horns, the head of another horse, and some indeterminate markings.

The Apse

In a space limited to approximately 30 square meters, with an average height of 3.5 meters, the Apse contains over a thousand figures. Among these, nearly 500 are animals and about 600 are geometric signs or various marks. The figures are distributed across the side walls and the dome-shaped ceiling without interruption. Their density increases from the entrance towards the back, reaching its peak in the apse’s recess, directly beneath the Well, in the most remote part of this chamber. The very soft limestone substrate partly explains this graphic exuberance. While the fame of Lascaux is primarily based on the paintings of the Bulls' Chamber, the Axial Gallery, and the Nave, the high number of figures in the Apse, as well as in the Passage, the Nave, and the Feline Gallery, highlights that Lascaux’s art is predominantly characterized by engraving.

The Collapsed Deer

The "Collapsed Deer" is one of the major representations in the Apse. Covering an area of nearly 4 square meters, this deer occupies the beginning of the vault near the entrance to the Nave, in a spot where the density of figures is minimal. It stands out due to the bending of its limbs tucked under the animal's belly, in a position that is anatomically unrealistic. On the antlers and limbs, some traces of brown paint remain, and black on the hooves. It is likely that the entire silhouette was originally painted. Two hook-shaped signs, one painted and the other engraved, cross the thorax. It is one of the rare figures where the cause, the signs that could resemble arrows here, and the effect, the collapse of the body, are concurrent.

The Well

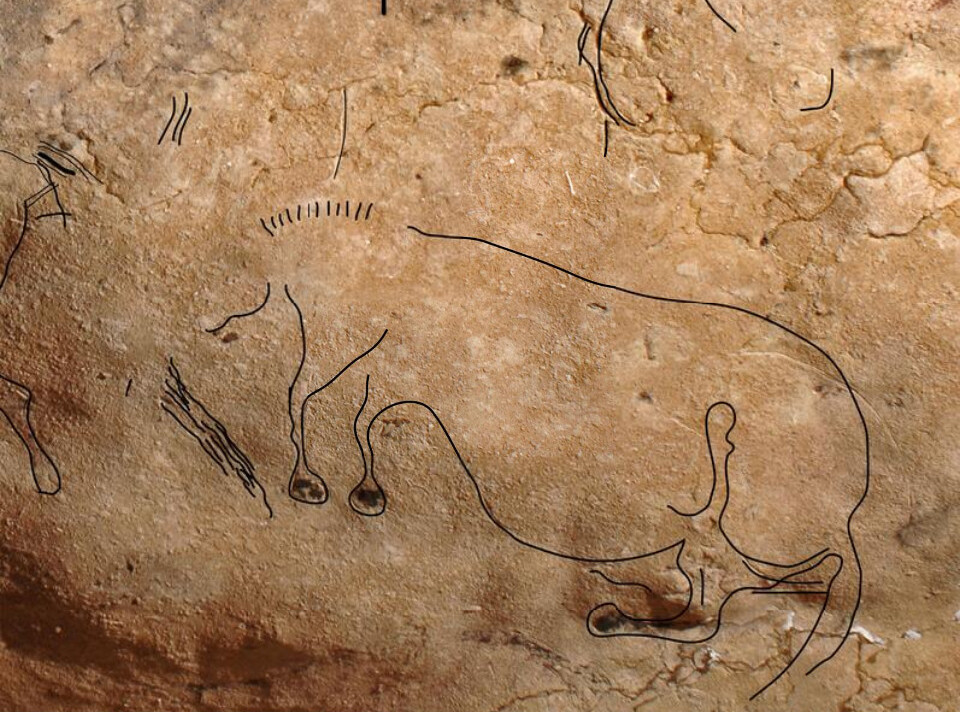

In contrast to previous sections—the Apse, the Passage, or the Bulls' Chamber—the Well contains only a limited number of figures, totaling eight. Four belong to the animal repertoire (horse, bison, bird, and rhinoceros), while the remaining three are geometric signs (dots and hook-shaped symbols). At the center of this composition, a human figure captures all the attention. On the right wall, there is a horse, and on the left wall, the other figures are grouped over approximately 3 square meters. This arrangement, made famous by its narrative potential, is one of the rare examples where the animation of the subjects and the chosen themes suggest a particular episode, hinting at the possibility of interpreting a message, hence the name "Scene of the Well" given to this panel.

Man and Bird

This human representation is the only one in this sanctuary. The torso and limbs are slender, with four fingers on each hand spread out like a fan. The genitalia is prominently depicted. The body is inclined at approximately 45°, likely a position induced by the bison's turning. Below this figure, there is an image of a bird perched on a stick. However, its silhouette is not precise enough to determine the species. The bird shares similar characteristics and possible connections with the human figure, including a head with similar features. In some primitive or ancient societies, birds often serve a psychopomp role, guiding souls.

Conclusion

This "Sistine Chapel of Prehistory" gained significant popularity with the public. So much so that the cave was forced to close its doors fifteen years after its discovery to protect it from the carbon dioxide emitted by tourists during their many visits. The ventilation systems installed for the tours also contributed to the deterioration of some pigments, causing many of the frescoes created thousands of years earlier by our ancestors to fade almost completely. Nonetheless, the opening of a replica of the cave in the 1990s, along with its numerisation, allows us to virtually explore this magnificent natural museum of cave art.